By Tami Klein

Posted in art, perspectives on life, design

We tend to think about video games as a form of entertainment, but over the last couple of decades there has been a growing movement that considers games to be a fully-fledged artistic and narrative medium. This relatively new medium enables us to explore topics and questions in ways that traditional media can’t accommodate.

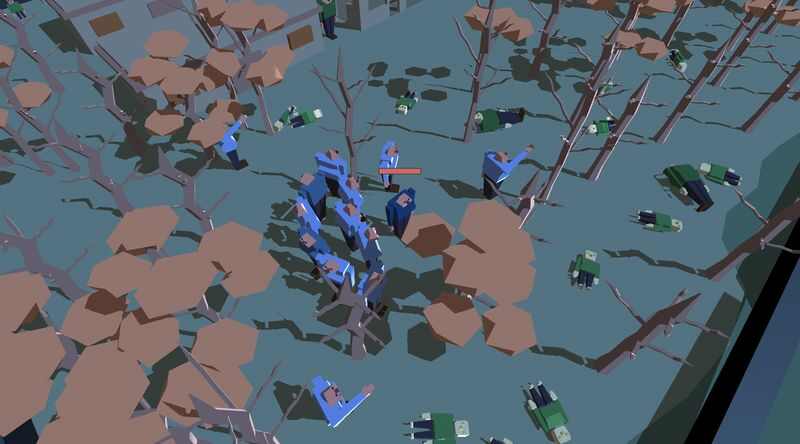

In my game, Shepherd, I wanted to explore the question of the player’s moral responsibility for her actions. In Shepherd, the player plays a leader who travels the world collecting and recruiting followers. The game world is also inhabited by enemies, who can attack and kill the player character. However, the player can’t attack the enemies directly, and must direct her followers to protect her character and destroy the enemies. What will the followers be willing to do in order to defend their leader? How far will they go in the war against their enemies? And what is the leader’s – that is, the player’s – responsibility for the followers’ actions when they become immoral?

Games as a tool to examine moral decision making

Unlike linear media such as movies and books, where the viewer / reader is only a passive observer, games are a unique medium in that they require the player to be an active participant. The interactive nature of games opens up a space for the exploration of moral and ethical questions that most other media are not equipped to handle. Games, by their definition, enforce a system of arbitrary rules on the participant, and there is no connection between the moral value of the actions performed inside the game-world and their moral value in the real world.

For example, if the way to advance in a game and collect points is to kill other characters, players will shoot others and will get a greater sense of accomplishment as their shooting becomes better and more accurate. Many studies have been conducted on the link between violence in video games and violence in the real world, and so far no significant connection has been found between the two. I believe that the main reason for that is that players tend to see the significance of their actions only within the isolated context of the game-world and the game’s system. Just as there is nothing wrong in “killing” the other player’s pieces in a game of chess, or in buying assets in a game of Monopoly, or in arranging the cards in the right order in a game of solitaire, we don’t perceive anything wrong in committing violent actions when the context of the violence is contained within the game.

The original idea for Shepherd came about after reading two books by Hannah Arendt: The Origins of Totalitarianism, and Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. According to Arendt, a totalitarian system enforces on its participants a set of rules, some of which are completely arbitrary. Obeying these rules is of the utmost importance in a totalitarian system, regardless of these rules’ morality or any other considerations. This set of rules is also what enables people to take the burden of responsibility off of their shoulders and transfer it onto the system: There is no need to think or to consider, only to obey. Any action that aligns with the rules of the system is fundamentally “right”, and anything else is “wrong”, even if the action itself or its implications and consequences don’t follow any accepted moral code or values.

In a game, players follow a set of rules. This set of rules in what defines the game: In chess, there is no external force that prevents players from moving the pieces on the board in ways not specified by the rules, or to add a dice roll in order to determine the success of each action. But once a single element in the game is changed, the game ceases to be chess. What defines chess (and any other game for that matter) is that players agree to accept and follow a predetermined set of rules. In real life, people can do anything that isn’t illegal. In games, however, the rules determine what can be done, and any other action is not allowed.

In much the same way as a totalitarian system, games place the players in a cognitive state that is susceptible to obeying authority and blindly following rules. Unlike a totalitarian system, a game is a safe and closed space that has no impact on the real world: When a character is killed in a game, it isn’t a real person but a collection of pixels arranged by lines of code. When the player leaves the game world, she is free to think about her actions and their consequences.

About the game

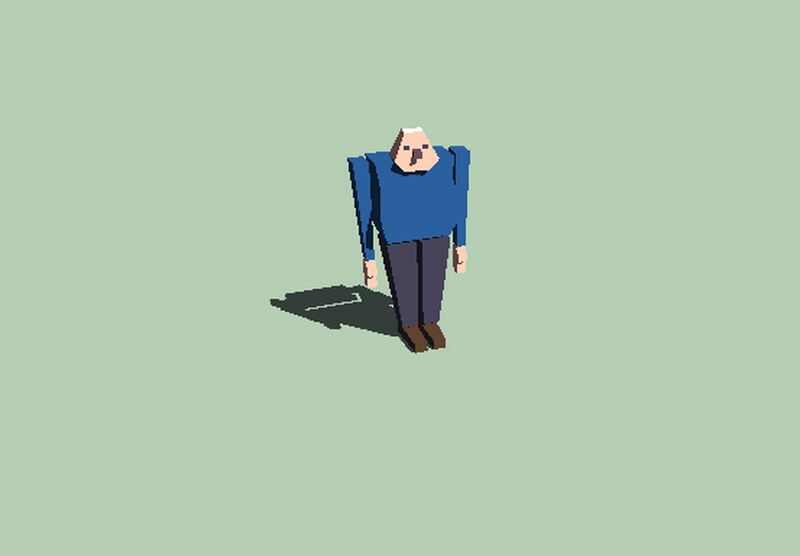

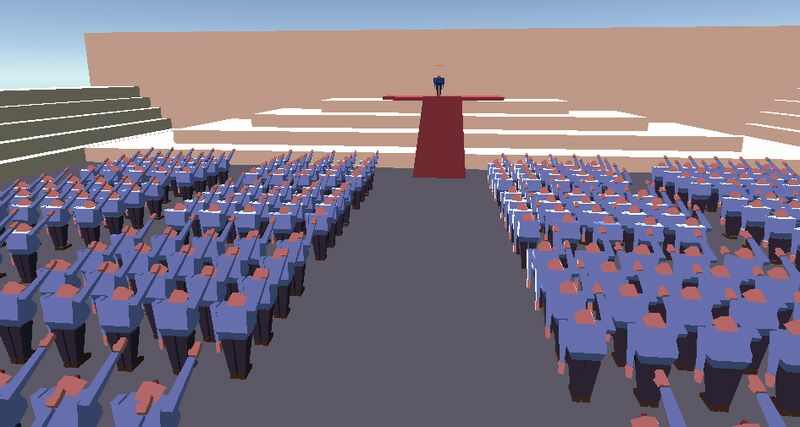

I created all of the game’s elements: game design, level design, programming, graphics, character design, and animations. The characters are meant to feel bulky and masculine, and walk in a way that resembles a military march. They lack any individuality, with the only difference between the player’s followers and enemies being the color of their shirts. The colors, as well as the simple shapes, serve a dual purpose: One is to create a world in which everything feels rigid, sharp, and geometrical. The other is to suspend the player’s understanding regarding the true meaning and nature of the game. Games that deal with similar subjects (such as Papers, Please and This War of Mine) often employ a dark and muted color palette to create a rough and oppressive atmosphere. In Shepherd, I used bright colors and a somewhat cartoony design to give players a set of expectations that don’t align with the game’s main theme. This reinforces the element of surprise and encourages stronger reactions when morally questionable events do happen in the game.

In the game’s first incarnations, it became clear to me that my main challenge as a game designer is to make players understand that their actions have moral implications. After seeing players play the early versions of the game, I realized that I need to create a plot that reveals itself gradually over the course of the game. Players start out by seeing themselves as “the good guy.” As the game progresses, they are presented with scenarios and actions that don’t align with that initial perception and make them consider the character’s role in the game world, and their own moral values.

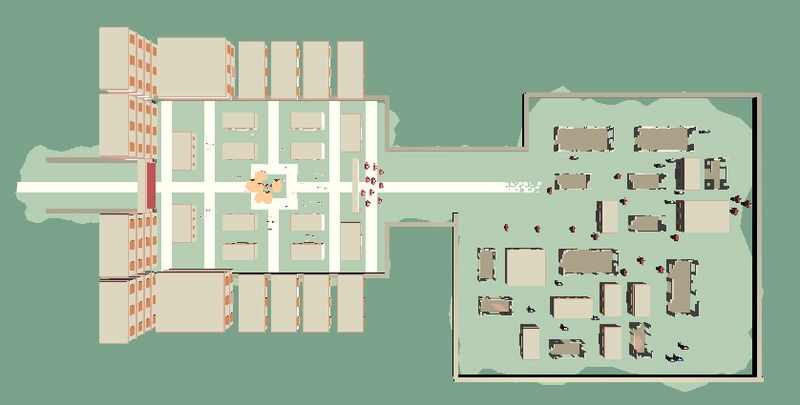

Shepherd has six levels, which I plan to expand in the future. Each level presents a new scenario with different challenges. There is no written text in the game. Instead, the plot is presented through visual and environmental storytelling, as well as actions that take place. The lack of concrete text makes the game’s overall story, as well as the main character’s identity and role, open to a level of interpretation.

In Shepherd, I tried to use games’ unique qualities as an interactive medium to test the limits of the player’s obedience in a safe environment. The ways in which players reacted to the game demonstrate that it succeeds in making them think about the double meaning of obeying rules: The player character as a figure leading others to commit immoral actions, and the player herself as a person blindly obeying the rules of the game.

______________________________________________________________

Shepherd was created as my graduation and thesis project as part of the Visual Game and Media Design MA at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. The game can be played for free on any computer browser (mobile phones are not supported):

https://gideonrimmer.itch.io/shepherd

Gideon Rimmer is a game designer, an independent game developer, and teaches courses on game design at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, Jerusalem. You can see more of his games on https://gideonrimmer.itch.io

Email: gideonri@gmail.com