By Tami Klein

Posted in perspectives on life, books

The English articles summarized below were published as:

“Sigmund Freud Confronts the Sphinx: Interview with George Sylvester Viereck” (London Weekly Dispatch, July 28, 1927)

“What Life Means to Albert Einstein: Interview with George Sylvester Viereck” (The Saturday Evening Post, October 26, 1929)

mahj.org

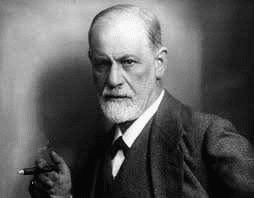

* – “What is your objection to the beasts?” Freud replied. “I prefer the society of animals infinitely to human society.”

“Why?”

“Because they are so much simpler. They do not suffer from a divided personality, from the disintegration of the ego, that arises from man’s attempt to adapt himself to standards of civilization too high for his intellectual and psychic mechanism. The savage, like the beast, is cruel, but he lacks the meanness of the civilized man. Meanness is man’s revenge upon society for the restraints it imposes. This vengefulness animates the professional reformer and the busybody. The savage may chop off your head, he may eat you, he may torture you – but he will spare you the continuous little pinpricks which make life in a civilized community at times almost intolerable. Man’s most disagreeable habits and idiosyncrasies, his deceit, his cowardice, his lack of reverence, are engendered by his incomplete adjustment to a complicated civilization. It is the result of the conflict between our instincts and our culture. How much more pleasant are the simple, straightforward, intense emotions of a dog, wagging his tail or barking his displeasure!”

“I am glad,” the journalist answered, “that my dog cannot read. It would certainly make him a less desirable member of the household if he could yelp his opinion on psychic traumas and Oedipus complexes! Even you, Professor, find existence too complex. Yet, it seems to me that you yourself are partly responsible for the complexities of modern civilization. Before you invented psychoanalysis, we did not know that our personality is dominated by a belligerent host of highly objectionable complexes. Psychoanalysis has made life a complicated puzzle.”

“By no means,” Freud replied. “Psychoanalysis simplifies life. We achieve a new synthesis after analysis. Psychoanalysis reassorts the maze of stray impulses, and tries to wind them around the spool to which they belong. Or, to change the metaphor, it supplies the thread that leads a man out of the labyrinth of his own unconscious.”

“On the surface,” the journalist responded, “it seems, nevertheless, as if human life was never more complex. And every day some new idea, put forward by you or by your disciples, makes the problem of human conduct more puzzling and more contradictory.”

–“Do you still place most emphasis on sex?” asked the journalist.

“I reply with the words of your own poet, Walt Whitman:

A woman waits for me: she contains all, nothing is lacking,

Yet all were lacking, if sex were lacking, or if the moisture

of the right man were lacking.

(From Walt Whitman, “A woman awaits me,” in Leaves of Grass)

* * *

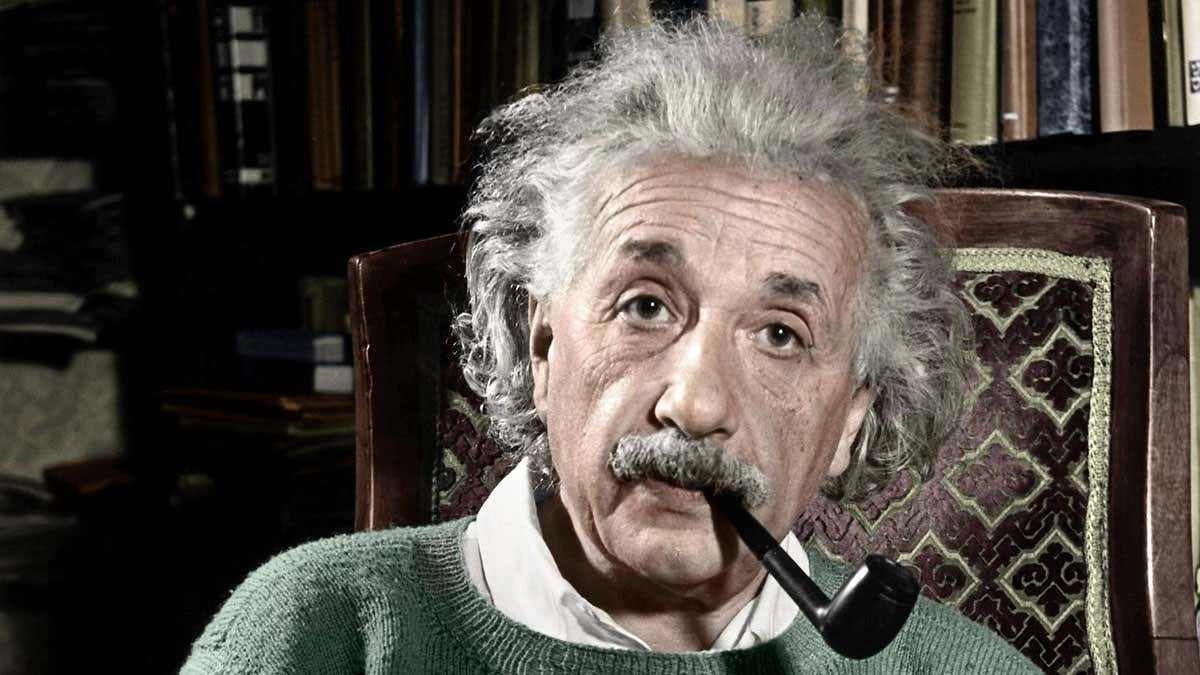

Viereck’s impression and opinion of Albert Einstein is apparent in the great appreciation he expressed, not only for Einstein’s scientific achievements, but also for Einstein’s remarks and worldview as a human being… Several aspects of Einstein’s perspective and personality come to the fore in the interviews:

“Einstein’s struggles with fate have left no bitterness on his tongue. Every line of his face expresses kindliness. It all bespeaks indomitable pride… He feels that he must preserve at all cost the integrity of his soul.”

“If I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music, I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music… I do know that I get most of the joy in my life out of my violin.”

“He is a sociable being. He loves quiet chats over his own dinner table with friends.”

Einstein was born in 1879 in Germany. He was educated in Germany, Italy and Switzerland, and had German and Swiss citizenship. “Poor, a Jew, a Socialist and a pacifist… Einstein conquers all obstacles, including his own shyness, by the sheer force of his cerebration.”

–”My own career was undoubtedly determined, not by my own will” (noted Einstein).

As a determinist, Einstein does not believe in free will. On the degree of freedom in human hands, he said: “I believe with Schopenhauer. We can what do we wish, but we can only wish what we must.”

“Do you mean to say that you did not choose your own career, but that your actions were predetermined by some power outside of yourself?” I asked.

“My own career was undoubtedly determined, not by my own will but by various factors over which I have no control–primarily those mysterious glands in which Nature prepares the very essence of life, our internal secretions,” Einstein replied.

“It may interest you,” I interjected, “that Henry Ford once told me that he, too, did not carve out his own life, but that all his actions were determined by an inner voice.”

“Ford,” Einstein replied, “may call it his inner voice. Socrates referred to it as his daimon. We modems prefer to speak of our glands of internal secretion. Each explains in his own way the undeniable fact that human will is not free.”

–The Illusion of Freedom

Despite the above, “as a pacifist and internationalist, Einstein is the very antithesis to the dictator,” emphasizes Viereck . “Although he denies the freedom of the will philosophically, Einstein resents any attempt to circumscribe still further the limited sphere within which the human may exert itself with the illusion of freedom.”

There is great wisdom in the illusion of freedom. This emphasis once again illuminates Einstein’s broad, deep vision of human behavior. Sometimes the illusion of freedom is central and even crucial to human conduct. History is undoubtedly able to point out numerous revolutions fomented by a sense that freedom was being restricted and gave birth to a new illusion of freedom that was, in turn, later shattered. Think only of the rise of communism, what came before and what came after, and the picture of desire, freedom and the illusion of freedom will become self-evident.

–What is your attitude toward the subconscious?

“Whereas materialist historians and philosophers neglect psychic realities,” Einstein replied, “Freud is inclined to overstress their importance. I am not a psychologist, but it seems fairly evident to me that physiological factors, especially our endocrines, are what control our destiny.”

It is very interesting to read Einstein’s attitude to psychoanalysis. In short, “However, it seems to me that psychoanalysis is not always salutary. It may not always be helpful to delve into the subconscious…”

Do not miss the story of Handel and the Toad, in which Einstein tells his mother about his perception of psychoanalysis. Is a fascinating story!

– Is there such a thing as progress in the story of human effort?

“The only progress I can see is progress in organization, Einstein replied. “The ordinary human being does not live long enough to draw any substantial benefit from his own experience. And no one, it seems, can benefit by the experiences of others. Being both a father and teacher, I know we can teach our children nothing. We can transmit to them neither our knowledge of life nor of mathematics. Each must learn its lesson anew.”

“But” I interjected, “Nature crystallizes our experiences. The experiences of one generation are the instincts of the next.”

“Ah,” Einstein remarked, that is true. But it takes Nature ten thousand or ten millions of years to transmit inherited experiences or characteristics. It must have taken the bees and the ants eons before they learned to adapt themselves so marvelously to their environments. Human beings, alas, seem to learn more slowly than insects.”

–Intuition, inspiration and imagination.

“If we owe so little to the experience of others, how do you explain the sudden leaps forward in science? Do you attribute your own discoveries to intuition or to inspiration?” I asked.

“I believe in intuitions and inspirations… I am enough of the artist to draw freely from my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination embraces the world.” Einstein replied.

–Nationalism and Race

“Do you look upon yourself as a German or as a Jew?” I asked.

“It is quite possible,” Einstein replied “ to be both. I look upon myself as a man. Nationalism is an infantile disease. It is the measles of mankind.”

“How, then,” I said, “do you justify Jewish nationalism?”

“I support Zionism,” Professor Einstein replied, “in spite of the fact that it is a national experiment, because it gives us Jews a common interest. This nationalism is no menace to other peoples.”

There is no doubt that all of us, including Professor Einstein, sometimes walk between the drops, because that is life. Einstein’s Judaism is unquestionably clear to him – he studied the Bible and Talmud as a child, never denied his Judaism and held the Jewish tradition dear.

Regarding race? “Race is a fraud. All modern people are the conglomeration of so many ethnic mixtures that no pure race remains,” Einstein noted.

Fate/determinism and… modesty, which we are yet to mention.

“I claim credit for nothing. Everything is determined, the beginning as well as the end, by forces over which we have no control. It is determined for the insect as well as for a star. Human beings, vegetables or cosmic dust, we all dance to a mysterious tune, intoned in the distance by an invisible player.”

* The boldface words in this article indicate points this writer wishes to highlight.

** The 2 interviews appear in a Hebrew booklet, published by – www.nahar.co.il