By Tami Klein

Posted in Yehudit Bar

Territorial colonialism has been known for decades, and in many places, for centuries. It is the ability of one people, with a completely different culture, to position themselves as a minority in a foreign territory with a entirely foreign culture and take control over it. This is not the place to recount the circumstances, needs and consequences – which range from the cruel to the benevolent…

As an example on the difficult end of the range, I would cite Cuba and Spanish colonialism. For the benevolent end, I quote an Indian friend born in Bangalore, India, and educated at an American university in India, “We were lucky to have been an English colony, what would have happened to us today if we hadn’t been?”

The concept of cultural colonialism has recently entered my consciousness, from several sources that are quite different from each other: 1) Dr. Mordechai Keidar, an Orientalist and historian, in a lecture that is part of the series “Coming to the Professors;” 2) in the brilliant – in my opinion – book Solaris by Polish-Jewish author Stanisław Lem and 3) in the world view of Jacqueline Kahanoff who grew up in Egypt, which was then a French colony, in the early twentieth century.

Be honest. Doesn’t it seem that the very fact that cultural colonialism is being considered from such diverse angles means that it may be able to teach us some useful wisdom.

First, in life as in life, nothing is either wholly black or wholly a shining light. Cultural colonialism was very beneficial to at least some of the population in Egypt and was certainly a great advantage for the people of India. Think, too, of the music that sprouted out of the diverse cultures of Cuba – the colonialist Spanish culture, the local Cuban cultures and the cultures of the unfortunate slaves who the Spaniards brought to Cuba for hard labor. This music evokes admiration for the way it integrates these cultures and also expresses the musical uniqueness of each one. The Cuban music created over the years is an extraordinary blessing and cultural contribution.

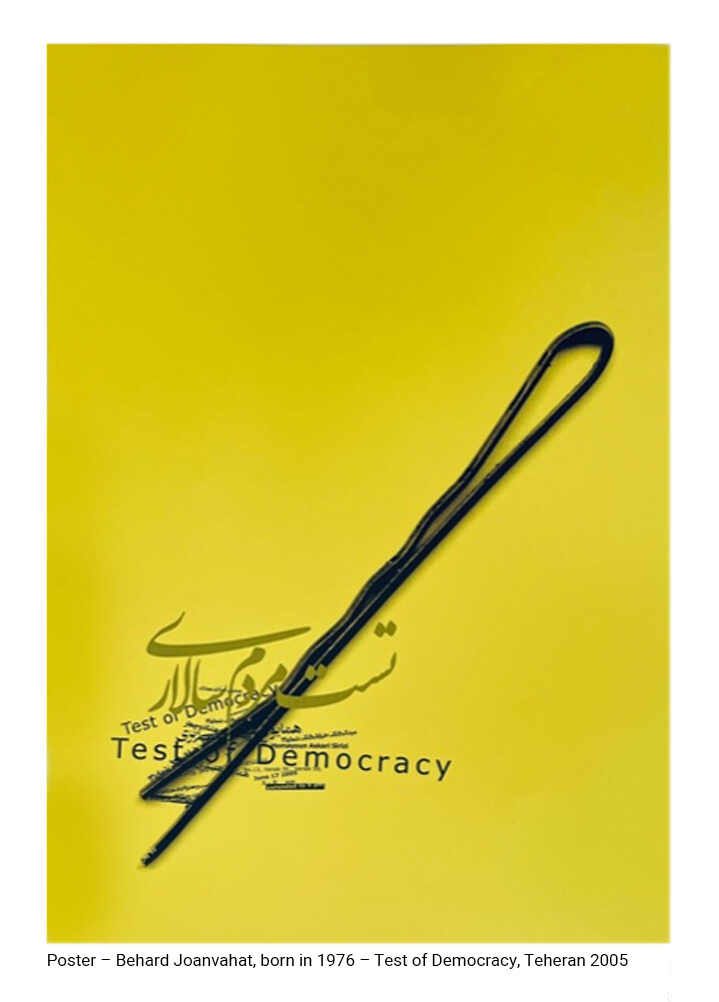

The desire to lead “democratic” cultures in countries where the source of power is tribalism certainly seems naive at best, and insufficiently deep when the step is taken lightly. Several reflections/texts come to mind, even from neighboring countries.

Perhaps the best question is the one I recently read in a text by Stanisław Lem (who was mentioned above):

“Some planets are said to be as hot and dry as the Sahara, others as icy as the poles or tropical as the Brazilian jungle. We’re humanitarian and noble, we’ve no intention of subjugating other races, we only want to impart our values to them and in return, to appropriate their heritage. We see ourselves as Knights of the Holy Contact. That’s another falsity. We’re not searching for anything except people. We don’t need other worlds. We need mirrors. We don’t know what to do with other worlds. One world is enough, even there we feel stifled” (Lem, Stanislaw. Solaris, p. 64).

“It’s what we wanted: contact with another civilization. We have it, this contact! Our own monstrous ugliness, our own buffoonery and shame, magnified as if it was under a microscope!” (Solaris, p. 65).

Following Stanisław Lem, I asked myself, “Where should we seek the roots of arrogance? Should we also to try to change human beings who are so similar to us? The critical question is ‘who appointed us?’” If we succeed in having it resonate within us, quietly but constantly, it will surely set us free for ourselves, to grow and enjoy what we already have.

Who has ever benefited – over time – from conflict?

To conclude this essay, let us consider the extent to which modesty is, perhaps, the most flattering ornament for any human being. How much beauty, softness, openness to dialogue would we experience, what contribution could we make to our environs and hence receive in return, if we were to walk quietly along the way life has presented to us, rather than based on ideologies and philosophies. The ancient Chinese knew to emphasize the importance of the road because there is no life without it.